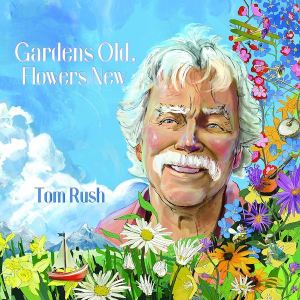

Tom Rush Photo by Gwendolyn Stewart

Tom Rush Brings Fresh Discoveries To Gardens Old, Flowers New

Lifelong singer, songwriter, and connoisseur of good songs Tom Rush releases his first album in five years, Gardens Old, Flowers New, on March 1st, 2024, via Appleseed Recordings. As it happens, this is also the first release of the year in Appleseed Recordings’ 25th year of existence, making for a particularly celebratory combination. It was recorded at The Carriage House Studios in Connecticut with Rush’s longtime friend Matt Nakoa who was also instrumental in persuading Rush to gather and record a new set of songs for release.

What we find on Gardens Old, Flowers New, are a selection of songs that have both older and newer songwriting roots, in keeping with the title, but also a wide arrangement of musical flavors accompanying them. That also speaks to a certain pleasant experience of wandering among diverse colors and tones that Rush and his collaborators bring to the garden and also the creation of a reflective space where each song gets its due share of attention. Something they all have in common is that pop of color, those surprising twists in terms of ideas and emotion that make Rush’s songs feel so fresh. I spoke with Tom Rush about what he thinks of songwriting, how he reacts to music, and how he makes cover songs his own over time.

Americana Highways: I understand that Matt was instrumental in getting you to record this album. Do you work best on albums when you have a limited, set time to do it, and you have to get from A to B?

Tom Rush: That’s a tough question. I have done that. I’ve been in a situation, decades ago, when there was a recording session coming up and I hadn’t finished the songs, and had to get them done. Sometimes that works, but usually the best songs just sort of arrive. I don’t know where they come from. I just try to catch them before they float out of the room again. I’ve done it a couple times, but I’m not good at writing a song specifically for a purpose.

I wrote one called “Shooting Coyotes” when there was a coyote-shooting contest out in Wyoming when I was living out there. It was kind of stupid, so I wrote a song about that. This town decided to hold this contest, and about a hundred guys showed up with a thousand guns among them, and they went out and blazed away for five days, and the award ceremony at the end was dampened because these hundred guys had come up with two coyotes. And one of them was disqualified because of the tire marks! I made that part up, actually. But I decided that I had to write a song about how glorious it was to shoot coyotes. That one I wrote on purpose.

AH: That reminds me of one of my grandfather’s favorite phrases, it was a “monument to their own arrogance.”

Tom Rush: There you go! But anyway, Matt did a great job coordinating everything and he’s a fabulous piano player. He’s also now a fabulous guitar player. When I first met him, he didn’t play guitar, but now he’s a monster. He’s on this album and he even plays the trombone. We were playing a gig at a place called The Tin Pan in Richmond, Virginia, and we went into a music store next door. Matt got all excited and said, “That’s the trombone I played in high school. I got really good at it!” When he asked how much it was, he shook his head and said, “Nah.”

But it turns out the woman who owns the Tin Pan used to own the music store and said, “I can get you that one half price.” So I gave it to him for Christmas a couple of years ago. It was cute, when he was taking it out of the package, he said, “It’s so cool! But I don’t remember how to play it.” But as he said that, he started playing it. So there’s a song on the album called “Nothing But a Man.” There’s a verse that says, “If I was a slide trombone, you could play me all night long…” And in comes the slide trombone.

AH: Do you think it’s mysterious how we don’t lose things like that? You can have twenty years go by and part of you is just waiting to do it again, as if no time has passed at all.

Tom Rush: I both agree and disagree. Someone can ask me to sing a song that I haven’t sung in a long time, and I don’t remember it, but my hands do. My hands remember how to play the chords, and then my mouth remembers how to sing the words. On the other hand, I took piano lessons for 12 years way back when and if I sat down at a keyboard today, I wouldn’t have a clue. It would probably come back a lot quicker than it did the first time if I took it seriously, though.

AH: It’s like that with languages.

Tom Rush: I think you’re right. I studied French for years and I haven’t spoken it in years, but if I did, it would come back. I read this thing about babies from age 18 months to three years old, which said that if they hear a language, they won’t necessarily learn it, but if they learn that language later in life, they will speak it without an accent. Something sticks in their little brains.

AH: That’s so interesting. It leaves a deep impression. That may have bearing on music, too, that if you hear certain kinds of music at a very young age, you might be able to operate in that mode more easily later.

Tom Rush: I think that’s right.

AH: Were you wide ranging when it came to listening to music growing up? A lot of people were that way due to the radio.

Tom Rush: Not really. My parents had a bunch of 78s. They had Paul Robeson, who was an operatic baritone. I loved his voice and I wanted to sing like him, but I couldn’t yet because my voice hadn’t changed. They also had Pete Seeger records. When I was in my early teens, the Rock ‘n Roll thing came along, in the late 50s. I was just bowled over by all that energy and all those fabulous songs.

It was a strange thing because there were all these incredibly talented musicians who were nothing like each other. There was Bo Diddley, who was nothing like Fats Domino, who was nothing like Elvis. He was nothing like The Everly Brothers. I loved all that stuff and just soaked it up. I had an older cousin who could play ukulele and taught me how to play the uke. Then, in the teen years, that turned into a guitar, because I thought it was more manly. I had a little band in high school. We were awful, but it was fun. When I got to Cambridge, for college, there was this huge Folk thing going on, and I just got sucked right into it.

AH: Why do you think you’re attracted to various types of music? Are you open to new sound directions in order to keep things interesting for yourself?

Tom Rush: Well, this is my 63rd annual farewell tour, by the way. I can’t tell you, really, why some music appeals to me and some doesn’t. I’m not vain enough to say, “If I don’t like it, it’s bad.” Listening to music, I don’t know why some stuff appeals to me and some doesn’t, but I first heard Joni Mitchell in this club in Detroit, Michigan, when she came in and basically auditioned for me. It just knocked my socks off and I was the first one to record her songs. The same kind of thing happened with Jackson Browne. I didn’t meet him, but I had heard demos. Elektra Records had his publishing rights and were playing demos for me. I thought, “That’s a good song!”

Again, I was the first to record his stuff, and the same with James Taylor. But I didn’t respond the same way to all of James’ stuff, and the same goes for Joni’s.

AH: I was wondering that. Because it sounds like it really is about the song for you, that particular song, and your reaction to it.

Tom Rush: I think, “I want to sing that.” My M.O., basically, is to learn the song off of a recording. Joni sent me a tape. Then after learning the song off of the recording, I won’t listen to the recording again. I let things drift off in whatever direction they want to take so that my version is not a copy-cat of the original. I want to have something new to say about the song.

AH: Do you find there’s quite a drift over time? Do songs take on different lives in that way?

Tom Rush: You should listen to my version of “Drift Away.” It’s very different. It’s acoustic. I think we have a cello on it, but it’s just one guitar, one vocal, and a cello. There are no screaming guitars on it. It’s a very sad song if you take away all that production.

AH: The emotion that’s buried in songs can come out when you start moving those pieces around. It’s amazing the transformations that can happen. Do you think there were intermediary states you pass through to get to the final version?

Tom Rush: For “Drift Away,” I was being told that I should record that song, so I went into my piano player’s studio with a band. We had drums, and bass, and keyboards, screaming guitars, and saxophone. It really sounded awful. I said, “Let’s leave off the saxophone.” And it got better. Then I said, “Let’s leave off the guitars.” And it got better. Finally, it got down to me, on the acoustic guitar. I said, “I like that.” It’s a whole different song. It has a totally different impact.

AH: So you’re waiting to hear it, and when you hear it, you know it? That’s it.

Tom Rush: That’s pretty much it. It’s the “goosebump principle.”

AH: You said earlier that you don’t sit down to write a certain song’s lyrics based on a mandate. Is it the same way with the writing of the music for a song?

Tom Rush: The music kind of comes along organically. In the best of worlds, I sit down in the morning before I’m really awake and strum the guitar a little bit. If I’m not really paying attention, I’ll say, “Oh, what just happened there? That was interesting.” Then maybe some words will be suggested to go with a melody line. I go from there. Sometimes the music comes first, sometimes the lyric comes first. My conception is that songs already exist out at some cloud at the edge of the universe and they come zooming in and float through my room. Again, my job is to try to catch them before they float away. Some songs come together quickly, and they are very often the best ones. Some are different.

I’ve got one song on this album where I wrote the words something like thirty years ago, and it only came together recently.

AH: That’s incredible. I was wondering what this method might mean for shaping songs. Do you let yourself edit and change things until you find “the right thing”?

Tom Rush: The song that I just mentioned is “To See My Baby Smile.” It was a love song that I wrote for my wife when we first met, and we parted ways a couple of years ago. The last verse is about that.

AH: Did you feel that it was not finished back then?

Tom Rush: Yes, I had a couple of verses, but it needed more.

AH: In what form did it exist all of that time? Was it in your head, or written down?

Tom Rush: It has a guitar part that I like a lot, and Matt had heard me play it over the years. He said, “That’s really good. You should finish that song.” I couldn’t think what the third verse was going to be, until it became obvious what the third verse was going to be. That’s Matt’s favorite song on the album.

Thanks very much, Tom Rush, for taking the time to speak with us. Find more information here on his website: https://www.tomrush.com/

Enjoy our previous coverage here: Interview: Tom Rush on New Release “Voices” Music as Indicator for Social Change, Harvard, and Production Anecdotes and here: REVIEW: Tom Rush “Gardens Old, Flowers New”