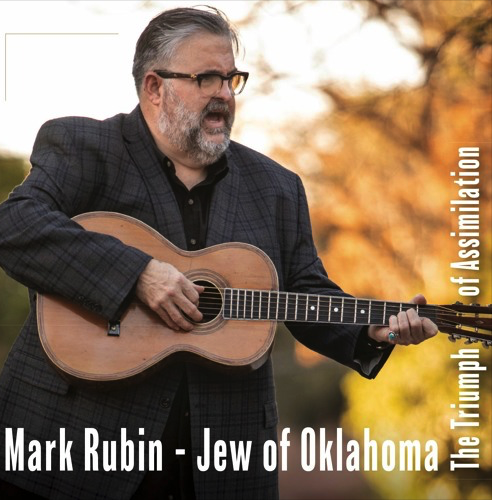

Mark Rubin’s work as co-founder, bassist and tuba player in the ground-breaking Roots and Punk band Bad Livers is what he’s most widely known for, but since 2015, he’s been in a developing role as a songwriter and frontman for his Jew of Oklahoma project. His third studio album under this moniker, The Triumph of Assimilation, is out on June 1st, and reflects Rubin’s desire to fuse his very Oklahoma and Texas “nurture” culture with the “nature” of his Jewish roots and his involvement in the Yiddish Renaissance’s Klezmer music scene. If that sounds like a natural goal for someone with such a varied background, it definitely hasn’t been a simple one for Rubin, but it’s one that’s come sharply into focus on the new album. The Triumph of Assimilation calls out the complexity of cultural identity in America and the bald-faced xenophobia and racism that Rubin has faced as a Jewish Southerner, but it also tracks the renewed threats of fascism and anti-Semitism in the South, where it now seems more “allowed” than ever in recent history.

Though some of the songs on the album are definitely “gut-punches” geared to raise awareness and inspire people to confront racism and fascism, Rubin approaches many of his experiences with humor and resilience, emphasizing the importance of trying to “fix” something in a broken world, even just small things, on a daily basis. Mark Rubin joined us to talk about the real world issues reflected on the album and what he hopes the future will hold.

Americana Highways: The title for this album has a number of possible feelings and tones to it. Is that ambiguity intentional? When I hear the word “assimilation,” I’m aware that it might not always be a good thing.

Mark Rubin: It’s supposed to be something of a tabula rasa. It’s an album title that’s like a game that I used to play with a lot of musicians. We’d write the album title first, then we’d write a record to match it. This title, The Triumph of Assimilation, has been in the rolodex in the back of my mind for almost 20 years now. Everything I’m doing right now has been kind of on my back burner for at least 20 years now, because I’ve been a sideman and a producer, and doing all the other things in the music industry that you can do aside from being on this side of the microphone. I never imagined that I’d be a frontman. Only now have those ideas come out. But the title for me kinda rings like Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will.

AH: That’s immediately what I thought of, too.

MR: To me, it just represents the Jewish experience in America. Jews have done it. They’ve assimilated entirely into American culture, but my query is, “To what end?”

AH: It seems like the assimilation in the cities has been light years ahead from the assimilation in more rural areas, as you have experienced. Is that accurate?

MR: It’s a different world. People may have a hard time understanding where I’m coming from when I talk about “the rural experience”. I’m in my mid-50s and when I was a small kid living in Oklahoma, your identity was chosen for you. If you were not a member of the dominant society there, you were not part of the mainstream. In my town, if you were Catholic, you were not part of the mainstream. Whether you wanted it or not, your ethnic identity was thrust upon you, and there was no way of getting out of that. Even if you wanted to assimilate into local culture, you really weren’t ever afforded that opportunity. You were always going to be an outsider, and in many cases, a pariah. However, when I was a young adult, I was able to move to the “big city” of Dallas, Texas, and you could meld into the larger scene. Then you could make a decision: Do I wish to retain this identity that was thrust upon me, or can I completely shed it?

This is a story that happened in my own family. My grandfather was the youngest of the kids in his family, the only one to be born in the United States. He made the decision that, even though he was the youngest, he would not go to religious school. He ran away from the family and his identity. It wasn’t until my father became a young adult himself that he returned to the faith.

This concept of being able to choose your identity is something that I’ve experienced on different levels in my own life in a way that Jewish people who live, say, in New York City, might take for granted or not be able to understand. Something that people also might not be able to understand is the amount of systematized xenophobia in rural America. There were a lot of humiliating experiences for my family in Stillwater, Oklahoma up to and including cross-burnings. There was the idea of constant race representation which is just tiring.

AH: I’m aware that you’re also maintaining a position that’s difficult from both sides because you’re between musical traditions. You’ve got the prejudice just for being who you are in the South, then you’ve probably got a fair amount of pushback from traditionalists in your own community.

MR: It starts with curiosity. There’s a phrase in Yiddish that translates, “The Little Red Jews” and that’s a phrase for “Jews from someplace we don’t know about, some far off place.” I used to get this line all the time. I’d meet somebody from New York or Chicago, where there’s a large Jewish population, and they’d hear my voice, and see my boots, and then they’d talk to me and find out that I was Jewish. They’d be completely incredulous, saying, “There are Jews in Oklahoma?” And my only response was, “Yes, of course. Where are you from?” We are a diasporic people. I had a song on a previous record called “Southern Jews is Good News”. The tune expresses this double marginalization which you get.

It’s unfortunate because I didn’t really have a musical home to go to anymore when you’re shown the door in the culture in which you were nurtured. And told that you need to go to the culture that is your nature. Then you get there, and you’re viewed with a certain amount of skepticism. In the 20 plus years that I’ve been working in the Yiddish Renaissance, I’ve more than earned my place. I’ve been welcomed with open arms, and I’m a genuine member of the community and I have nothing but love for it, but it was a tough slog at the start there. One of the big stumbling blocks in all that is that I was not raised around, nor do I speak, the Yiddish language. Living in Oklahoma and Texas, you’re just not exposed to it, and that is the core of the Jewish cultural revival.

My specialty is in the musical end of it, in Klezmer music. I’m a bassist and a Tuba player and I ended up going to events, becoming an instructor, and teaching internationally. I’ve had quite an accomplished career as a Klezmer musician, which has been wonderful, but what I’ve neglected all that time in the music of my nature, is the music of my nurture, which I grew up playing and flows out of me the most.

But that’s what this record was built around, taking Yiddish poetry that might otherwise only be understood by a few, and bringing it out, like the work of Mordechai Gebirtig. That’s where the track “It’s Burning” comes from, taking these messages that I feel were super-prescient, written on the cusp of the devastation of fascism in Europe, and trying to present them now during what I fear could be the rise of fascism in our own country.

AH: Thank you for providing that context. I was wondering how much the message of this record was influenced by the experience of living in America from 2016 onwards and it’s pretty clearly there.

MR: I’m new to the singer/songwriter world, having been a working musician since I was 15 years old. I’ve only started writing and performing songs since 2015. With each of my releases, and this is my third, I tend to feel that I’m honing my craft. These pieces kind of fell out of me, in many respects, though I did include one from my earlier catalog because I felt it was super-important. I felt it was important to tell the story of Leo Frank. Not many people know that chapter of history.

AH: Yes, that is incredibly harrowing. I learned about this from your song, then I went and read more about it. It’s chilling.

MR: If anything at all, if adding that tune on the record makes anybody go look it up, I’ve done my job. We’re talking about tunes on the record that are each gut-punches so far!

AH: I was really horrified by the role that Folk music played in Leo Frank’s story, that there was a musician who was perpetuating the violence. Have you come across that much?

MR: It wasn’t just any musician, it was a venerated musician. There are Jewish people I know who venerate him and play his tunes. Fiddlin’ John Carson looms large in the world of Modern Old Time music today and very few people know the story about that. I often see memes about the “healing power of music,” but no one interviews the string quartet who played at the Dachau death camp. No one talks about Fiddlin’ John Carson playing on the courthouse steps at Leo Frank’s trial. Music was used to whip up the crowds to help lynch him. Music is indeed powerful, but it is indeed a double-edged sword. It’s a tool and it can soothe you, and it can also make you think, but it can also be very hurtful and I’ve seen it used in many different ways in my travels and in my years as a musician.

AH: It’s always been used to incite mass movements. It’s always been used for triumphalism. It’s been used by dictatorships and other regimes to secure the unity of the people. Even traditional and Folk music have been used to try to influence people and convince them to follow certain leaders.

MR: I would hope in my own small way that these gut-punches can break through and help folks think or make some positive impact towards progress.

AH: Do you see possibilities for improvement right now in the way that people treat each other in this country?

MR: My Rabbi says two things to me that sound contradictory, but they are actually the same. Firstly, he says, “The more things change, the more they are like the 15th century.” But he also says, “Because I’m Jewish, I have to assume that everything is going to be fine.” What he really means is that when something bad happens, we have to assume that something good is going to come from it. That’s our job. So, am I hopeful? Yes, you have to be hopeful, otherwise you won’t be able to get out of bed. But also, I’m coming from that traditionally Jewish place of sardonicism that is hopeful, but also assumes everything else. I was raised with this concept of “tikkum olam,” that is, “to repair the world.” It says that when you wake up in the morning, you find the world broken, and it’s your job and duty to fix it. You don’t have to fix the whole thing, but find something to fix. It’s just as simple as that. It’s about personal responsibility and understanding that the whole thing is broken. Find the little thing that you can affect and change, and I think that is what creates hope. It’s in the work. In being able to do something. It’s like Geburtig says in the poem and song, “You have tools.” So you pick up the bucket and put out the fire. It is doable.

There’s also another Jewish concept that I feel is essential. And that is, that if you’re sitting under the shade of a fruit tree and enjoying the fruit, you have to understand that the person who planted that tree never got to do that. They did it so that you could. So it’s encumbent on you to plant a fruit tree so that someone else can. You’re thinking of the future, and there’s got to be hope in that. So why am I releasing a record that is so obviously uncommercial and challenging in its content? Because I am hopeful that someone will be cheered by its concepts and it will make them want to affect change. Or it will make someone stop and think for a moment and want to affect change. Or maybe it’ll just make them laugh about trying to keep Kosher in the South.

AH: Is this album, potentially, your fruit tree? Are you aware that there are young people coming up in the South of Jewish heritage who might need to hear this?

MR: There is more and more bald-faced anti-Semitism in this country because people are allowed to do it right now. I have a student who comes to me to learn about Klezmer music. I have a salon here [in New Orleans] called “Tuesdays are Jews-days.” Young Jewish people come and we have a little salon, though this was all before the pandemic. One of my students had to run to a gig down at the bar, and I couldn’t make it, but that morning at about 3:30 in the morning, I got a text from the guy. This is a little emotional for me to tell this story.

In New Orleans, the bars are kind of small, so there’s not a lot of distance between the audience and the musicians. At this particular bar, the front door is right by where the band sets up. My man told me that he had been packing up his gear by the door, and there was a tip jar near the door. A gentleman came up to him and said, “Hey man, I didn’t quite catch your name.” And so he said what his first name was. Then the guy said, “I didn’t quite catch your last name.” And then he said his last name, which was a very typically Jewish last name. Then this patron of the bar laid into a long anti-Semitic scree, screaming invective at him, and waving money over the tip jar at him, saying, “I bet you want this, you little birdie Jew.” He said that he went out to his car and just sat there for hours. He said there were two things that upset him the most. The first was that he just didn’t know what to do. And then the second thing was that nobody came to his aid.

AH: Wait, not even his bandmates came to his aid? Were they there at the time?

MR: Yes they were. So if you ask if there are young kids here in the South who need a hand, or who haven’t experienced this…There are a lot of young Jewish kids who have never been challenged the way that I was challenged as a kid and they don’t have these skills. They don’t know what to do. Maybe they lack a certain amount of pride around their identity and have taken it for granted for a certain amount of time. People may have a hard time understanding this, but hate crimes are on the rise, and in places where there aren’t many Jewish folks, Jewish folks are an oppressed minority. It may not feel that way to folks who live in big cities, but it’s a different experience elsewhere.

AH: Are you concerned that the young people who have these experiences will just leave the South?

MR: That’s not what we’re going to do. That’s the whole point, that we’re not going to do that. We’re going to be Southern people because we are from here. We’re going to celebrate our Southern culture and we’re going to be Jewish. I think that’s one of the clarion calls of The Triumph of Assimilation.

Find Mark Rubin’s music here: https://www.jewofoklahoma.com

1 thought on “Interview: Mark Rubin ’s Jew of Oklahoma Project ‘The Triumph of Assimilation’ Addresses Anti-Semitism On The Rise”