I can’t say that I ever ran into Glenn Frey but he once ran by me. I was sitting behind the stage at the Yale Bowl during a July afternoon on the Eagles The Long Run tour. As the band finished its last encore, men were running up the steps following Glenn Frey. As the band’s de facto leader abounded up the steps near the wooden benches of the storied stadium, he was a few feet from me, still singing and snapping his fingers. “Ooie baby…won’t you let me take you on a sea cruise.”

It seemed so surreal and unexpected as if the band were still playing. After the tortuous making of The Long Run, here came Frey to see in a joyous few seconds. Frey was like the kid from Detroit whose voice you can still pick out in the chorus of Bob Seger’s “Ramblin Gamblin Man.” Frey was followed by Don Henley and guitarist Don Felder. I spotted manager Irving Azoff who at the time had more facial hair than he did in the Eagles documentary The History of The Eagles. The rumor going around was that Azoff had told the concert promoter if he didn’t produce a cashier’s check for $600,000 the band would not go on.

Frey would pack some of his own Detroit muscle during one of the many Eagles reunions that were to come. There’s that scene in the documentary where Frey, recasting himself like a modern-day character out of his own western Desperado, demanded that Don Felder sign a contract “by sunset” if he wanted to still be in the band.

I was still thinking of Frey snapping his fingers to “Sea Cruise” on another July Day nearly four decades later as I stepped foot into Nationals Park in Washington, D.C. As I remembered him singing the chorus of the Frankie Ford classic, it was with the still sobering realization that Glenn Frey is no longer with us. Glenn Frey, already gone.

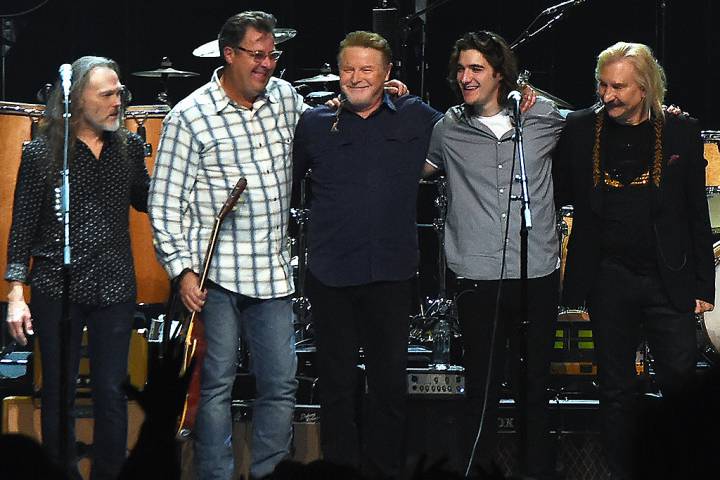

Onstage in his place is son Deacon and guitarist Vince Gill. Deacon, at times eerily similar to the younger long-haired version of his father around the same age, has been instantly likable since the band put him onstage at the Classic East and West shows. Deacon has less of the moxie of his gunslinger dad and Gill is one of the more amiable guys you’ll meet. When a distraught Ashley Monroe showed up at Gill’s front door one time, he invited the friend and songwriting partner in, motioning to his wife Amy Grant, “Amy, looks like we’ve got a wounded bird here.”

If there was still a feeling of making the new guys feel at home, it might as well have been Joe Walsh to break the ice. “Well hello…how ya doing?” Walsh said, striding out to the mic with a twinkle in his eye hinting that he just might be still crazy after all these years. “Please welcome Deacon Frey.”

The younger Frey wasted no time and jumped headfirst, reprising “Take It Easy” the song his father sang and that launched the Eagles. With his image framed against the smoggy yellow sky and palm trees of Hotel California era Los Angeles, he instantly was an Eagle.

The other new guy Vince Gill cut in to lead the second verse that Bernie Leadon once sang. The song helped commercialize the country rock born out of the Byrds, Flying Burrito Brothers and contemporaries like Poco.

“I’m going to sing one my dad use to sing if that’s ok,” said Deacon, adorned in a Washington Nationals jersey, as if he even needed to ask. When he got to the verse in “Lyin’ Eyes” about what a woman can do to your soul, the whole band came in at the same spot that Randy Meisner and Bernie Leadon did back in the day. Gill, Frey and guitarist Stewart Smith traded licks back and forth as a portrait of a smiling Glenn Frey came up and stayed put for just the right amount of time before it inevitably faded out.

I was thinking of the review of The Eagles in Circus Magazine. Reviewer Janis Schacht gave it the highest accolade, a full heart which meant she loved it. Instantly I was intrigued and taken upon hearing “Take It Easy” and the follow-on song “Witchy Woman,” the melody hooking me but whose mysteries I was still too young to understand. It was probably that review as much as any that led me to write about music a few years later and still a major reason why I get looks while I am taking notes at a stadium show.

And here I was, still transfixed by the tantalizing intro to “Witchy Woman” with its bluesy, funky groove evoking the desert and cutting through the sweaty city night, feeling like it was swinging with horns, the marvel of modern keyboard technology.

Timothy B. Schmit told everyone how coming to D.C. reminds him of the early days in Poco. Schmidt looks youthful and spry and still has the golden voice in “Love Will Keep Us Alive. In “I Can’t Tell You Why” the sultry keyboards, Henley’s drums and Stewart Smith’s guitar made the stadium feel like an intimate nightclub.

When Gill and the younger Frey joined, Schmidt seemed like he passed on the baton as the “new guy” in the band. Schmit has the historical significance of having replaced Randy Meisner in both Poco and the Eagles.

Rusty Young, a founding member of Poco who played with Meisner in Colorado, was in town at the Birchmere a few weeks earlier and teased that Schmidt played “Keep On Trying” in Poco and then tried making it a hit in the Eagles.

Rusty Young would tell you it was hard to have a friendly rivalry with the Eagles when Don Henley was so serious. But he is able to laugh that both Poco and the Eagles have in common is that they both opened up for Yes, the progressive English rock band that just happened to play in D.C. after Poco’s date and just before the Eagles landed.

When Henley came center stage early in the set after playing drums during “One of These Nights,” it was like he was standing at the lectern. The English major from North Texas State Univeristy was like the history professor who announced in a monotone delivery that over the next two and a half hours, we would hear songs spanning four decades, emphasizing the importance of playing them in that they act as a journal and diary for a “long, strange trip.” Henley praised Glenn Frey for his great contribution to the canon of popular music. Delighted by having Deacon onstage, he welcomed Gill, another “old boy” and one of America’s best songwriters.

Gills version of “Take It To the Limit” wore like an old sweater. But Gill was supported with the stellar harmonies and a stadium full of voices with the song’s punchline ingrained in their sub-conscious. Across the river, Gill held court for years at the Birchmere as part of the Time Jumpers. Now he was in center field a few weeks after the MLB All-Star game and the Stanley Cup made its way through the nation’s capital.

Throughout the night I’d seen shirts from different eras. There was a “Farewell Tour from 2003.” Another was from “The History of the Eagles” tour, the tour that brought back multi-instrumentalist Bernie Leadon. Leadon is long gone and living in Nashville. But Gill’s presence and picking during the opening song “Seven Bridge Road” evoked the Leadon era when the Eagles were fronted with mandolin, banjo and acoustic guitars.

It was Leadon whose tenure in the Flying Burrito Brothers and early Eagles is responsible as any of his era to inspire country rock and what we now commonly put in the big tent of Americana.

Baseball players talk about the ghosts in ballparks like Yankee Stadium and Fenway Park. Sitting in the cavernous stadium, it was too new to have ghosts but hard not to go back and think of another era and the role nation’s capital played in Americana’s evolution. It was here that Emmylou Harris, who grew up in nearby Prince William County, met Gram Parsons and whose harmonies lace the epic album Grievous Angel. Parsons died before its release but its legend has only grown over the years.

The burgeoning roots scene of the early Seventies in Washington centered around the club called Cellar Door. if you ever go to a Live Nation event, check the property addresses of Cellar Door Drive that are all named after the famed club.

Harris was doing a pop folk set when Georgetown student Walter Egan first saw her at the Cellar Door. It was a music scene with names of the likes of Bill Danoff, Roy Buchanan, Nils Lofgren and Roberta Flack. “She was easy to like,” Egan once told me. “When Chris Hillman approached her about Gram she didn’t know who he was. I was a big fan at that point so I played her Sweetheart of the Rodeo and The Gilded Palace of Sin.”

“And so he traveled along, touch your heart, then be gone,” sang Bernie Leadon in “My Man,” a tribute to Parsons from the Eagles’ On The Border album. “Like a flower, he bloomed till that old hickory wind called him home.”

“This time thing is weird,” Henley commented during the set seemingly criss-crossing decades from one song to the next. He took us back to 1974 and the band’s days in Laurel Canyon when friend J.D. Souther helped Frey and Henley finish what become their first number one record, “The Best of My Love.” Henley was slightly grainy, maybe weathered, but still sounding soulful. Then he was launching into another Souther song, the upbeat “How Long,” that was the single marking the band’s initial comeback after a fourteen-year hiatus.

Henley commented that the success was both a blessing and a curse, an oft-repeated theme explored in the docudrama of the History of the Eagles. Souther was a pivotal figure in Eagles-lore helping write “The Best of My Love,” “Lyin’ Eyes,” “Heartache Tonight” and “The Long Run.” Souther was also the first name in a trio he fronted with Richie Furay and Chris Hillman in one of the original “supergroups” as they came to be called in the Seventies.

Which takes us back to the present. Hillman, the original bassist for both the Byrds and The Flying Burrito Brothers, is playing this year with Roger McGuinn and Marty Stuart on the 50th anniversary of Sweetheart of The Rodeo, the project that is largely the marker for the advent of country-rock.

Perhaps we would just call it Americana now.

Rusty Young, who carries on with Poco and is signed to Blue Neon along with “Peaceful Easy Feeling” songwriter Jack Tempchin, told me he likes the name.

“I think it’s great. It all sounds like Gram Parsons to me. It’s too bad Gram wasn’t still around because he would have appreciated that all these guys were trying to imitate him.”

2 thoughts on “The Eagles Then and Now & The Ghosts of Americana”