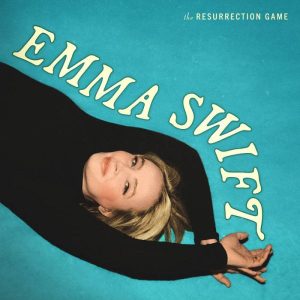

Emma Swift’s Resurrection in Gray and Blue

Emma Swift’s new album, The Resurrection Game, unfolds like a series of letters written from the far edge of an emotional winter. It is a record of desolate beauty and delicately held hope, the sound of someone who has passed through collapse and found something luminous in what remained. Swift does not sing to escape the pain that shaped these songs; she sings to make meaning of it, or as she said, “to alchemize the experience. To make the brutal become beautiful.”

The album is Swift’s first collection of original material, following her acclaimed 2020 release Blonde On The Tracks. Where that album allowed her to inhabit Bob Dylan’s language and spirit, The Resurrection Game is unmistakably her own voice in full. It was written in the wake of a devastating psychological breakdown that left her hospitalized in Australia and struggling to reconstruct a sense of self.

“One of the positive things that came out of it was I really just fell in love with music again afterwards,” she said. “I could take an experience that had made me fairly broken and pull myself back together by making music.”

The songs move between private confession, philosophical reflection, and storytelling, but always with the clarity of someone refusing to hide from what hurts. Her lyrics carry a confessional intensity shaped by her admiration for poets like Robert Lowell and contemporary writers like Maggie Nelson. She writes with the understanding that personal truth can be terrifying to look at directly.

“For a lot of my twenties and a good part of my thirties, I loved art and music but I was afraid to put my hand on the table,” she said. “This album is really about overcoming that fear and singing how it feels to be me.”

The recording was shaped in an atmosphere as evocative as the music itself. Swift and producer Jordan Lehning traveled to Chale Abbey on the Isle of Wight, a 16th-century stone barn repurposed into a residential studio. The days were short, the skies gray and sea-torn, the rooms drafty and old. Swift stayed in a haunted pub nearby. The musicians lived together at the studio, stepping into the music each morning under the same damp, timeless light. “It felt like removing everyone from their normal life,” Swift said. “It was a very conscious decision to be somewhere remote. It made the music feel like it existed outside of time.”

Lehning’s arrangements lean into that sense of being slightly untethered from the present. Pedal steel sighs like memory. Strings drift like mist around the edges of the frame. The songs are lush but never ornamental, dramatic but never forced. The sonic touchstones range from Scott Walker to Harry Nilsson to the dream logic of David Lynch’s cinematic worlds. Swift and Lehning listened to Angelo Badalamenti’s film scores as a guide to atmosphere.

“We were trying to create a dream world,” she explained. “To be a little out of step with time.”

The thematic heart of the album lies in the title track, where Swift considers resurrection not as a triumphant rebirth but as the ongoing work of living with what one has survived. “Resurrection Game changes with the seasons,” she said, “and with the phases of our life, our relationships, what we identify with. I wanted to use the word game because as I get older, grief and loss step in. Approaching change with a kind of playfulness has become necessary.”

Part of that clarity emerged through the global disorientation of the pandemic. “We got a little closer to death as a culture than we usually sit,” she reflected. “I was too terrified to leave the house for months. The way that I came up against my own mortality changed me.” The songs carry that knowledge: mortality is not theoretical, meaning is not guaranteed, and hope is not sentimental. It is a choice renewed daily.

Yet there is tenderness here, too. “Nothing and Forever,” in particular, reconciles Swift’s romantic, somewhat naive optimism with the darker nihilism of the world around her—and, playfully, with the philosophical stance of her husband, musician Robyn Hitchcock.

“He’s the nothing and I’m the forever,” she said, though the song suggests something more universal: that we all exist between what ends and what endures.

Even at its most desolate, the album refuses despair. Swift does not mythologize her breakdown. She references it plainly, even humorously, as something real that happened to a real person.

“I would rather say, yes, I had a fully fledged nervous breakdown, than pretend I just disappeared for a while,” she said. “The more we share what really happens, the more compassion and kindness we can extend. Nobody gets five gold stars for life.”

The Resurrection Game is a record for people who have known loss and still want to believe in love. It is for those who understand that hope can be quiet, that rebirth is rarely dramatic, and that we do not return from the underworld unchanged. It is a work of grace shaped from ruin, made on her own terms, with candor, subtlety, and a voice that holds both the ache and the shimmer of resilience.

Find more information here on her website: https://www.emmaswift.com

Enjoy our previous coverage here: REVIEW: Emma Swift “The Resurrection Game” Where the Brutal Becomes Beautiful

For story ideas and suggestions, Brian D’Ambrosio may reached at dambrosiobrian@hotmail.com