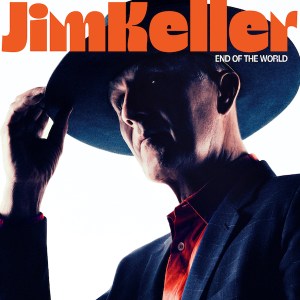

Jim Keller photo by Jimmy Fontaine

Jim Keller Finds a Way To Keep On Moving at The End of The World

Jim Keller is a New York-based songwriting musician who will be releasing his album, End of the World, on October 24th, 2025, co-written with Byron Isaacs (Lumineers, Levon Helm) and produced by Adam Minkoff (Graham Nash). For Keller, it’s his fourth album in five years, and builds on his time with the band Tommy Tutone, as well as many years he’s spent in other aspects of the music world.

Keller’s albums have been hailed as carefully written, with each song likewise precisely crafted, and End of the World takes that approach and redoubles it. Taking on the heaviest and strangest aspects of modern life, each song turns ideas around with directness and compassion, while finding a way to keep on moving. They leave their energy behind with the audience, just a hint of the energy from the enjoyable group jam sessions in which Keller’s songs are usually born. I spoke with Jim Keller about the environments in which his music life thrives, and consequently, where the songs come from, as well as about some of the strange benefits you just might find at the end of the world.

Americana Highways: The way that these albums come about is very personal, through jam sessions. Are you also someone who is wanting to play these new songs live coming up?

Jim Keller: I’m doing dates in Nashville, Austin, San Francisco, LA, and New York. There are a handful of dates. And I’ll probably go to Europe. But it’s not like I’m blanketing the US. I just pick towns where I know that I have an audience, and where I have friends and musicians. Often what I do, like when I got to Nashville, is that I use my players in Nashville to play the dates. The same thing in California and Austin. So it’s a kind of party. When I can have a party, and it can have this looseness to it, I do it. For me, at this stage of the game, it’s about, “Where can I have a really good time, with a bunch of great players, and an audience who wants to be there?” That’s kind of how that works.

AH: That’s really sweet that it’s like a reunion for you in these different cities, where you all get to hang out.

JK: Oh, that’s also a big part of what I do. As you mention, for the last twenty years, I have a jam session at least once a week in my studio. I’ve literally been doing it at least once a week for a long time. Part of the joy of where I am at in my career is that I get to play with all these great players. It gives me a chance to work out new tunes, but it’s also about what’s happening, and who’s in the room that day. All the players know that, since some are gone on tour, and then they are gone for a year, and then they come back in.

But then, when I can go to other towns, it’s the same. It’s a great joy. It’s fun for them, and it’s a way for me to just share that joy of just playing for playing’s sake, and not just to put on a show.

AH: That’s wonderful to hear, since that’s an approach that’s less common, though it’s a little more common in roots music.

JK: That’s true, though I think it’s also more common among my Jazz buddies. There’s all ages, too, in my group. There are guys who are 22, and there are guys who are 70. One thing about music is there’s no “sell by date.” They are busy, and they are busy doing what they get paid to do, but coming into this room, they say, “Wait, there’s no agenda?” It offers an opportunity for people to cut loose. Nothing leaves the room in terms of audio and video.

In some ways, it’s an extension of me playing gigs. I always have people sit in. There are incredible musicians in this country, it’s insane. Every generation there are intuitive, great players. It makes me happy when people play together who don’t know each other, too. That’s where all the records come from for me, from that process.

AH: I agree there are so many ridiculously talented musicians out there who are just getting by, doing their own things. It makes me really happy to hear that people form musical communities which help them keep doing this for longer in their lives, supportive communities. It isn’t always about public release or performance, but about adding richness to their lives.

JK: It’s the big payoff, that community. Fortunately, I don’t have to rely on touring, since it’s a lot of work. I think it’s a little more attractive when you’re young.

AH: How do your sessions contribute to your new songwriting, given they are so free-flowing?

JK: I don’t remember my process early-on, when I was in my 20s, but when I started writing when I had the band Tommy Tutone, which was Tommy Heath and me, I brought my songs in and Tommy has a great rock ‘n roll voice. So that’s where that started for me. The songwriting process, which I love, had always been part of my life, even when I stopped playing, which I have for certain parts of my life.

But it always starts there, when I bring those scraps or whole songs into a jam session. Along with just playing whatever, I’ll toss this stuff out, and just start playing it, and see how it works with whoever is in the room. We’ll be in the middle of relative chaos, and I’ll suddenly hear something, then I’ll start calling chords out, and I’ll hit the “record” button on my iPhone. I’ll just record snippets of things that I’ll then take home, because I know that something was happening in that minute that was cool. Whether that turns into a whole song, that depends, but it’s either samples of songs that exist, or snippets of things that come out of nowhere.

For me, it’s the subtley of whatever the groove is, that has created something unique, so unless I can record, and hear the vibe that was created, I won’t know where to go back to. So it’s really helpful to have the recording part of it.

AH: Do the jam sessions contribute to, or at least encourage the multi-genre aspect of your songwriting? If different people are playing all the time, they are bringing different genre accents in, presumably, from their own inclinations.

JK: I think that’s part of it. Some of the records that I’ve made over recent years have really been based on me sitting with my acoustic guitar, writing. There’s a consistency that comes from that, so when I’m playing with more players, or working with a producer on a record, like on this record, Adam Minkoff, they bring other stuff to the table. You might not be surprised, but people might be surprised how many directions a three-chord song can go, depending on how you produce it and arrange it.

So a lot of that comes from what happens after the writing, really. It can come from the original jam sessions, but it’s often who I’m working with in the studio, and what puts a smile on my face. I’m making the album for me, and the handful of people who are working with me, so there’s no need to limit myself.

AH: Is it every hard to choose between alternate song directions on that end?

JK: You kind of go with whatever’s working that day. If it works, we go in that direction. I think it’s partly that I’m working with musicians who are so talented, and who I can trust. If everyone in that room knows something is working, they don’t even need to say it. If it works, that’s the record you make that day. You follow that. There aren’t that many songs where I say, “You have to do this.” I take the lead from the room, whether it’s in the jam session or the recording studio. That doesn’t mean that I haven’t worked out, meticulously, the song.

I work with Byron Isaacs, who’s in The Lumineers at the moment, and between the two of us, we spend hours of joy nit-picking about one word. Or it can happen, in a minute, that we write the whole song, then we’ll go back and work on one word for a month and a half. That’s what it is to create the three-minute haiku that is a pop song. That’s a never-ending well of intrigue for me.

AH: I was going to ask how the co-writing worked. It sounds like you have someone with a similar mentality, someone who likes the nit-pick just as much as you do.

JK: Yes! It helps that he lives down the street. I’m very fortunate. Sometimes we’ll write songs together from scratch, but what usually happens is that Byron comes over, and he’s as much editor as co-writer. With a pop song, there can be one line can change it from being another song to actually something that’s “okay.” “Good” is hard. “Really good” is really hard. “Great” is impossible. That line can be almost impossible. But to have someone like Byron in the room with me, he’ll throw a line out, and it could just be that one little thing, that actually brings you into that song. That’s what it’s all about, whether you’re writing or performing, when you draw someone else into that story. We do love that process, and I’ve been very fortunate to have Byron with me in the room over the years.

AH: I feel like the songs on this album often deal with difficult things, but seem to find a position of equanimity within that. Your internal state has a stability to it.

JK: It’s hard for me to say, since I don’t go at a record with a concept, and I really don’t analyze, or try not to. It’s a question I never like. When I have to write PR about every song, it’s the worst thing in the world for me. In a way, it spoils it, because the song is whatever it means to somebody else.

But a lot of stuff in there, whether it’s articulated or not, is impacted by what’s been going on in the country, ever since the last 8 years. There’s just no question about it. There are a handful of songs where that’s clearly the emotional place, whether I’m dealing with it sarcastically, or not. Then there are always songs that are more personal, that tap into years of experiences and situations. There are always a combinations of those things on the albums, and then there are songs that are just rock ‘n roll songs!

AH: Like with a lot of rock or pop music, we get a really positive feeling, too, with these songs, like human life encountering difficulties, and finding the energy to get through them. Are you someone who thinks about positivity in terms of the music you create?

JK: It’s kind of who I am. I’m not Lou Reed. There’s a song I wrote that starts with the line, “Get up every morning with a smile on my face, spreading joy all over the place.” But that’s one of the saddest songs I’ve ever written. Even in me dealing with something that’s a very sad topic, there’s the sense of this outlook, and I am that person, for better or worse.

On this record, there’s a song called “The End of the World” that’s kind of a comedy. When I wrote that, it’s when everything was going on that’s going on now. It’s tragic. But even in that song, there’s a lightness to it that balances it, really. I feel like I’m already saying too much about this song! [Laughs]

AH: Well, then I’ll say something as the audience, about what the song meant to me…

JK: You’re allowed!

AH: Okay, well that song made me think about the half-empty and half-full idea, as dark as that is in this context. Because it’s true that when a structure falls down, it’s also true that the flaws in that structure also fall down. When a slate is wiped clean, it takes both the good and the bad with it.

JK: I think you’re right. It’s funny, one of my favorite lines in that song is about everybody telling all the secrets that they know. Well, it’s the end of the world, so the hell with it!

AH: As real-life tragic as it can be, I have known people who felt “woken up” by major life and world events that made them tell their feelings more openly to friends and family members. I also like how far that song goes, because I feel like it goes longer, and with more lyrics, and more feelings than it might have done. It could have stopped sooner, but keeps pushing.

JK: I like where it ends up! [Laughs]

Thanks very much for chatting with us, Jim Keller. Find more information here on his website: https://www.jimkellermusic.com/