By the mid to late 1960s, England and California had become the world’s most-talked-about musical hotbeds. However, earlier in that decade and in the latter part of the 1950s, Philadelphia was a much bigger disseminator of rock and pop. Besides being home to Dick Clark’s influential American Bandstand TV show, the city housed a handful of record labels that collectively accounted for a large portion of the era’s hit singles. A new anthology demonstrates that it takes two fully packed three-CD sets to showcase many of them.

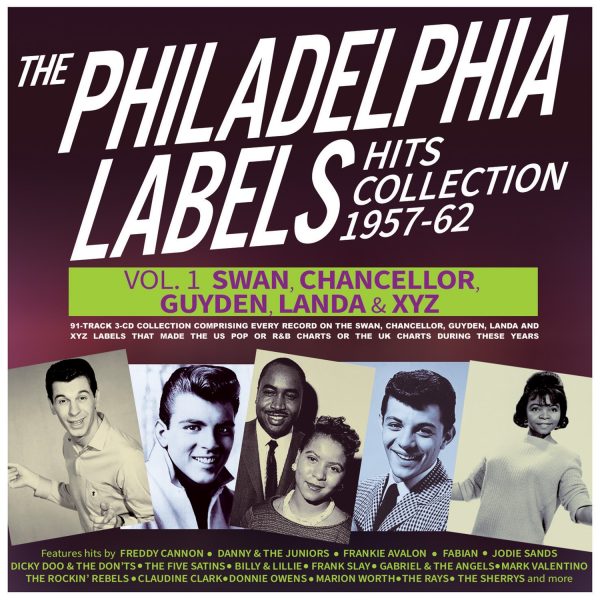

Volume One of The Philadelphia Labels Hits Collection 1957–62 contains 91 tracks, most of which were originally issued by Swan, Chancellor, and Guyden. Volume Two adds 94 selections, most of which Cameo, Parkway, or Jamie first released. Nearly every number in both collections made the U.S. pop or R&B charts or the UK charts, and quite a few became major hits. Dominating the programs are songs by Frankie Avalon (26 numbers), Freddy Cannon (19), Duane Eddy (19), Bobby Rydell and Chubby Checker (20 and 15, respectively, plus one together), and Fabian (10).

As many of the tunes by these and the other featured artists suggest, this period in rock history wasn’t exactly overflowing with creativity. In fact, some of these performers appear to have been more concerned with accumulating royalties than with creating something new. One hint of that: while later acts like the Beatles strove to experiment and top themselves with each new release, many of the artists showcased in this collection seem to have been content to try to find new ways to profit from past successes.

Some tried to cash in on another singer’s hit with a cover. Bobby Rydell, for example, issued a recording of “Volare” in 1960 that echoes Domenico Modugno’s chart-topping original version from two years earlier. Others delivered “answer songs,” like Jo Ann Campbell’s “(I’m the Girl on) Wolverton Mountain,” a response to Claude King’s big hit, “Wolverton Mountain.” (Rydell made it to No. 4 with his cover, but Campbell barely broke into the Top 40.)

Still others simply strove to copy their own past successes. Dee Dee Sharp made the Top 10 with “Mashed Potato Time” and again with “Gravy (for My Mashed Potatoes),” for instance, while the Dovells followed the smash hit “Bristol Stomp” with the less-successful “Bristol Twistin’ Annie,” and Checker followed the massively successful “The Twist” with similarly styled, dance-themed numbers such as “Let’s Twist Again,” “Slow Twistin’” (a duet with Sharp), and “Twistin’ U.S.A.”

Such tendencies don’t mean there’s nothing of value in The Philadelphia Hits Collection, but this stylistic grab bag of rock, R&B, pop, and novelties is also a mixed bag quality-wise. The nadir is Fabian, who had some good material to work with but was groomed for stardom solely because of his looks and admitted that his records were electronically enhanced to make up for his vocal shortcomings.

Also subpar are the tracks by such artists as Avalon, Rydell, and Dicky Doo & the Don’ts, all of which help to explain why the end of the 1950s and the first few years of the 1960s came to be known as a fallow period for rock. At least some of their songs are catchy and pleasant and might bring back memories for those of a certain age, but they sound decidedly dated and are not what anyone would call musically significant. A large handful of them are downright inane.

Mixed in with such tracks are more than a few winners, however. They include the performances by pioneering electric guitarist Eddy, who recorded influential instrumentals such as “Rebel-’Rouser,” and singer/guitarist Cannon, whose “Tallahassee Lassie,” “Palisades Park,” and other high-energy rockers were bright spots on early-1960s radio.

Also excellent are the doo-wop and rock hits by the Rays (“Silhouettes”), the Orlons (“Don’t Hang Up,” “The Wah-Watusi”), the Rockin’ Rebels (“Wild Weekend”), and Claudine Clark (“Party Lights”). In addition, you’ll find many likable obscurities that barely dented the charts and don’t tend to show up in oldies collections, such as the Four Dates’ “I’m Happy,” the Playboys’ “Over the Weekend,” and Maureen Gray’s “Dancin’ the Strand.”

James McMurtry’s Latest Ranks with His Best

The Black Dog and the Wandering Boy is the latest release from singer, songwriter, and guitarist James McMurtry, who has issued about a dozen albums since 1989. The album, which underscores his status as one of America’s most underappreciated folk/rock/Americana artists, was co-produced by the singer and Don Dixon, who is known for his work with R.E.M. and the Smithereens. It features Dixon on guitar, bass, and trombones as well as backup from such other performers as Bonnie Whitmore of the Whitmore Sisters, BettySoo, and James’s son, Curtis.

The Texas-based McMurtry sounds a bit like Warren Zevon and shares the late singer’s rock sensibilities; the son of famed novelist Larry McMurtry, whose books include the Pulitzer Prize–winning Lonesome Dove, he also shares his father’s literary talent. The difference is that while the father’s tales fill hundreds of pages, the son delivers his evocative, sharply honed vignettes in about five minutes or less.

You don’t have to venture beyond the intriguing first verse of a McMurtry song to sense his talent as a lyricist. “South Texas Lawman,” which evolved from a poem by a family friend, begins, “South Texas lawman, he brings ’em back alive / He hunts quail from horseback, and he cheats on both his wives.” “The Color of Night,” meanwhile, opens with, “I was lying on the shop floor in a pile of broken parts / Thought I heard drums in the distance, but it was only my heart.”

Another standout is “Annie,” one of the best songs about 9/11 since the ones on Bruce Springsteen’s The Rising. Sample verse: “I never thought much of the younger Bush / He never seemed to have a clue /He sat there smiling with that children’s book / While they decided what to do.”

Then there’s the title cut, which begins, “The black dog and the wandering boy come around every night / The wandering boy never gets any older, the black dog doesn’t bite. That song, incidentally, was inspired by the album’s cover drawing, a pencil sketch of the singer as a child by novelist Ken Kesey, to whom the singer’s stepmother was married for 40 years.

Bookending the program are two powerful covers that sound tailor-made for McMurtry. “Broken Freedom Song,” by Kris Kristofferson, concerns “a soldier riding somewhere on a train / Empty sleeve pinned to his shoulder / And some pills to ease the pain.” Jon Dee Graham’s riveting rocker, “Laredo,” is about “living in a motel called Motel out on Refinery Road [where] we shot dope till the money ran out.” The song includes lines that allow listeners to fill in the picture with their imaginations: “There’s a stain in the [car’s] trunk, man, that’ll never ever, ever come out,” sings McMurtry, “And it’s shaped like a small dark something.”