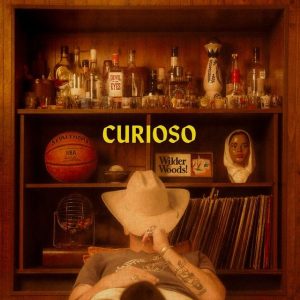

Bear Rinehart photo by JM Collective

Driven To Keep Creating: A Life of William “Bear” Rinehart

Son of a preacher, William Rinehart grew up in Seneca, South Carolina, at the high foothills of the Appalachians. His mother taught piano lessons. His father played the trumpet. Music was a mixture of gospel, rural hillbilly, bluegrass, and rock and roll, all slammed together. At age 13, his job on the weekends was to vacuum the old ugly carpet at the church and he liked it when the congregation left their instruments strewn about. In between spells of cleaning, he would pick up a guitar and study the sheet notes.

In high school, most of his friendships formed through the trading and sharing of cassette tapes. Rinehart was drawn to the harmony and twang of bluegrass and raspy singers such as Joe Cocker, as well as odder entities such as a band called Jump Little Children, an indie crew from the Winston-Salem area. He also was enticed by the righteous strength of Otis Redding and Ray Charles and the way that gospel mantras seemed to raise people up from down places.

“Gospel was something people were using to lean on during their tough times,” said Rinehart, frontman of Needtobreathe and solo artist under the name Wilder Woods. “The music I heard felt like that to me. As a kid, my brother and I would tape the radio in the bedroom, and it was sort of our lifeline. It made life worth living and easier to get along.”

Rinehart played wide receiver on the Furman University college football team. Though his favorite lyricist was Adam Duritz of the Counting Crows, he listened to a lot of “weird and foreign stuff” on college radio, especially WUOG, a student-run station out of Athens, Georgia. Rinehart and some friends organized Needtobreathe during his freshman year and by the time that he graduated the group was performing approximately 50 shows a year. It was a frenetic and exuberant period: he burned and sold compact discs out of the backseat of his car. Football was the number one priority. Music was a close second. School work ranked third.

“When I first started, I didn’t have any comparison of what was possible or what you shouldn’t do,” said Rinehart. “I live close to Nashville now, and you could feel self-conscious without knowing it. But the music environment in South Carolina, that wasn’t like that. In the South, there is high BS meter. If it isn’t coming from a genuine place then it doesn’t seem to connect. My point of view is that my music has always been small town in its own way.”

There was an old drugstore converted into a cheap basement bar in Greenville called Carpenters Cellar and a couple days after Rinehart saw The Black Crowes in concert, he bought an electric guitar and tried to play it in front of a crowd there. In his words, it went “horribly,” but soon after the group found its niche – a crossover blend of redeeming and upright Christian messages and satisfying rock and roll – and developed a following.

“We’d have 150 people packed at Carpenters Cellar and I fell in love with performing there,” said Rinehart.

There was another bar that taught Rinehart an integral lesson about the nature and definition of success in the music business called The Handlebar (also now closed).

The first time that Needtobreathe sold out The Handlebar, approximately 400 tickets, Rinehart said that he and his bandmates felt as if they’d “made it,” and that they’d “found their people.”

“You come to understand that you are not making music for everybody. In a city like Boston you need 200 people to show up to make it feel great. You don’t need everybody in Boston to be there. The wider you try to make it, the more you are missing.”

Solo Shining, Striving

Rinehart, aka Wilder Woods, released his latest solo studio album, Curioso, in February. He said that his approach to music as both a solo artist or as a member of the group is similar: don’t look to others or other places for validation; allow the different collaborations between writers, players, and singers to collide organically and strike their own chemistry.

“When you have a new formula of people collaborating in different areas, like on this record (including musician Jim James, singers Maggie Rose and Anna Graves, and songwriter Trent Dabbs), the thrill is finding the magic that is inside of that. I did the songwriting part mostly on the front end and brought them to a band and workshopped it. We did live takes. Bass, drums, guitars, tracked at once, in a classic sort of way. I appreciate the speed of that and the simplicity to the way that we approached it. Songs have their original meaning intact.”

On Curioso, Rinehart, 44, felt as if he was easily able to lose himself and slide into a magical position, where the vocals resounded with an emotional hunger and strength. He said that his top priority was to have the vocals serve the song, not to overpower or attempt to outshine it.

“I used more variety as to how I approached it, from super quiet to a big belting thing,” said Rinehart. “I focus more on that these days. Is it believable? Do I love it? Some songs are asking for a delivery, some are about the melody, or some emotion matters more, or some need space. I try to cut a vocal as soon as I write the song, if possible; retaining the emotion of why I wrote it is still there.”

While pronunciations and meters and parallel vocal timing are all worthy recording considerations, Rinehart said that the biggest check that he imposed on himself with Curioso was whether or not the finished version sounded as if he had truly expressed something.

“I think being too self-conscious is the biggest challenge,” said Rinehart. “So I try to focus on, do I love it? Does it reveal a frailty? Does it express the real insecurities you have? Can you hear these things when it comes across the track or not? I would like to think that you can on the stuff that was just done.”

Rinehart, who is the father of three boys under the age of nine, said that on the new recording he was able to extend himself to a spot where he was able to faithfully let go of his self-distrust, entering a sacred place where art cannot be reversed, questioned or stopped. Nevertheless, the potential of a masterwork is something that he can’t help but dwell.

“I’m always feeling as if it is not the best that I can do,” said Rinehart. “That’s what drives me to keep creating. Thinking that the perfect record is still out there.”

Thank you very much for chatting with us, Bear Rinehart. You can find more information on Wilder Woods here on the website: https://www.iamwilderwoods.com

Brian D’Ambrosio may be reached at dambrosiobrian@hotmail.com