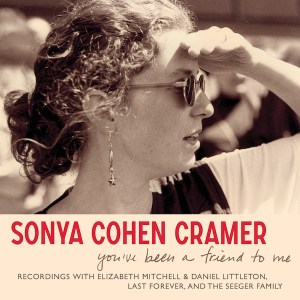

Dick Connette interview. Sonya Cohen Cramer photo by Reid Cramer

Dick Connette on Sonya Cohen Cramer’s Luminous Life and Work

Smithsonian Folkways recently released the album Sonya Cohen Cramer: You’ve Been a Friend To Me which shines a light on the work of late singer Sonya Cohen Cramer who was the daughter of John Cohen of the New Lost City Ramblers and Penelope Seeger, the younger sibling of Mike, Peggy, and Pete Seeger. Additionally, Sonya’s godfather was Folkways founder Moe Asch and she’s well known for her many graphic design contributions to Folkways titles.

While Sonya worked in multiple creative fields, her most concentrated musical work was as a member of the band Last Forever with Dick Connette and Scott Lehrer, which focused on American Folk and popular music. This project drew her into recording and live performances, leading her to develop a project of her own in music for the first time, and was a defining part of her creative life. I spoke with musician and composer Dick Connette, who operates the record label and studio StorySound Records with Scott Lehrer, about the music brought together for the new album, and he also kindly shared his impressions of Sonya as a person, as an artist, and as a close friend.

Americana Highways: What affected the timing and choices in putting this album together of Sonya’s work?

Dick Connette: I’m close to her family and it means a lot to them. It took some years to gather up the strength to even think about beginning to collect Sonya’s singing and put it out into the world just because there was so much grief. But they gathered it up and I was glad to work with them on it. It seemed good to do this with Smithsonian because she belongs there for a number of reasons and Folkways is an institution. Sonya’s husband and proposed it to them, and they love her because of her long history with them and her graphic work. Elizabeth Mitchell and Daniel Littleton, who she recorded with in those last sessions, are also Smithsonian artists, so it was a natural fit for them, and they jumped on it.

AH: I know arts people who work in various different fields their whole life, and when that happens it can be hard to consolidate their legacy, for lack of a better word. They may be known in multiple fields, but it can be hard to pull together one definitive statement of who they were and what they accomplished. Sonya did such outstanding graphic work as well as music, so that makes this a great crossover to have it released by Folkways.

DC: Yes, and her father John Cohen had the same issue. His work was all over the place in terms of writing, playing with the New Lost City Ramblers, his photography, his photography book. He taught painting at SUNY Purchase. He both suffered and profited from his involvement in lots of activities, and the same thing was true of Sonya. Though it was the case in both her design work and her singing that she didn’t really try to draw attention to herself. She didn’t really make a big deal of it. She just did it. If she had a path, it wasn’t so easily defined in her artistic endeavors.

Once we started working together, she was in Brooklyn for a while, and we were rehearsing together and developing material. We were performing once every two or three months in small clubs in New York with a four-person band, including ourselves. Then, at one point her husband Reid was going to go to grad school in Austin, and she was going to go there with him. When she announced this to me, I shed a tear or two because I was losing my way of working. She assured me that we could continue to work, and we did. In fact, there is a design element in the album package that’s a collage where Lead Belly features prominently, and she gave it to me the next time we saw each other as a pledge that we would continue to work together. Reid included it as part of the package.

AH: What was it like working together after that time?

DC: Once they moved to Austin, we kept working, and she’d come to New York and we’d record and work on stuff. But I missed hanging around with her, so I’d go to Austin every year for SXSW just to hang out. Sonya would give the baby to her husband, and we’d don the all-access passes, and go to the clubs! [Laughs] We’d drink those margaritas that came out of the hose and have a great time.

Around the time that our second album was finished and would be coming out on Nonesuch, she had laid out her plans for our future and said, “Our first album was a strong statement, and our second album builds on what we did on our first album, but our third album is going to be luminous!” I took this as a daunting proposition. Maybe she was confident of being “luminous” on the third album, but I wasn’t sure how to get there. It occurred to me that what was luminous was the life that she’d created for her family with her daughter, and son, and Reid, and the life she built. There was a luminosity that didn’t have to do with any particular art project. That was just who she was.

AH: I remember someone once telling me that there are people whose art projects are themselves, and they are their greatest works of art. It’s a mysterious thing. Even if you don’t know what their work is, there’s often something about them that’s luminous.

DC: Yes, there was nothing remotely bitter about Sonya. I think what you’re describing is that the art is merely one emanation, and the art is coming from the life and the life is not defined by the art.

AH: Yes, that’s a really great way of putting it. Something I don’t really know about is how these recordings on the album came about. Was she making recordings from time to time as a collaborator with other people throughout her life, and this is a selection of those, or was there more intentionality in these particular recordings?

DC: There are two songs on the collection where she sang as part of the Seeger family, from the Christmas Songs for Children and Animal Folk Songs for Children. She would do that just because her dad was John Cohen and her mom was Penny Seeger. When the Seeger family was getting together to sing these songs, everyone would find a place and just sing along. That was part of Pete’s mission, to bring people in and sing. The song “When I Was Most Beautiful” was one that Pete just decided that Sonya would be great singing on. Actually, Sonya and I recorded a version of it also. That was just a one-off.

The songs with Daniel and Elizabeth are eight songs at the end of the album. In the last year or so of her life, she was diminished and fighting off the cancer. Her close friends weren’t so much trying to rally her as keep her doing things that they knew meant a lot to her. In effect, they intervened and kidnapped her. [Laughs] They went over to her house and said, “You know those songs that you love singing? Let’s record those songs.” That was in the last year of her life. They set up these sessions and made them possible out of love for her and the desire for her to keep expressing herself. I think it’s beautiful what they did. After they made those eight recordings, and Sonya died, they went on and kept working on the recordings, mixing and adding some instruments, just to shape them up.

AH: Did you know about those recordings at the time they were happening?

DC: I think that the last time I saw Sonya, she came to New York with her husband and her daughter. We went to the Highline park and Sonya and I sat on a bench. She had her laptop and she said, “Do you want to hear what I’m doing with Daniel and Elizabeth?” I said, “Sure! Plug me in!” She had headphones, and she played one song. I said, “You got anything else?” She played another. That was the last day that we spent together, was her playing me the songs. She kept playing me songs until she ran out of songs.

It was clear that she was surprised and happy that I really liked hearing them so much. I did because many of the songs were ones we had done or talked about doing, like “You know that song about the two sisters? The one with the wind and rain?” It was just great to hear her singing. That’s a fond memory, of sitting there on that bench, with me wearing the headphones, and her waiting for me to finish one song so she could go and play another one.

AH: Was Sonya easy to work with? Hearing her collaborations, she seems very sensitive to what other people are doing, and adapts to that.

DC: I’m not surprised that you can hear that. She was very giving. Even though she didn’t push herself forward, she had a fierce sense of her own identity and what mattered to her. In terms of working with me, when the opportunity came around to work with me, she saw it as a way of establishing herself outside of her family.

She expressed to me that she loved her Uncle Pete, and her family, but she didn’t want to be subsumed into them. For a lot of the family, they would all hang around and sing songs together. She did participate in that, but she didn’t want to make that her life. In our project [Last Forever], I think she saw a way of both having a regard from where she was coming from, but to make something that was her own.

AH: I’m happy to hear that she was looking for something of her own and continued in that project.

DC: It’s what she wanted. She wasn’t turning her back on so much of what her family and what she had learned, but she was doing what she wanted to do. I was just fortunate to be part of that and lucky to have found her.

AH: What was your first show together like?

DC: It was always clear that she had a great voice and was tuned in. Initially, I set up a show about two months ahead. She didn’t have much experience of recording or performing, though I’d been doing it for a long time by then. I thought, “She doesn’t know what she’s getting into, but she said, ‘Yes,’ so we’re going to go ahead and do this.” It was me playing a harpsichord kind of instrument, a dulcimer, and a harmonium. Then we had a woman who was playing violin, and Sonya was singing. We rehearsed and we did the show. We have a video tape, and I’m glad that we have it, because she looked like she’d been doing it her whole life. She was so confident, so relaxed. Her performances were so confiding and generous. It was beautiful. I thought, “It wasn’t her, it was me! I didn’t know what I was getting into.” She was just there from the very beginning.

But this shows you what kind of person she was, that her mother came up to me after the show and said that she’d never heard her daughter sing that much in her entire life.

AH: She was keeping it to herself, or hadn’t brought it out to anyone.

DC: That’s how little she was showing herself off to her parents. It felt wonderful to me, since that meant a lot to her mom to see her daughter expressing herself and performing. She seemed like she was born to be there in that kind of performance. It wasn’t a showy performance. We all sat down when she decided to, and that might have been part of her folk background. She also very much liked performing with her shoes off! She preferred to have her feet on the ground.

AH: Did you all ever disagree creatively in terms of songs or interpretations?

DC: I brought a ballad to Sonya once, an old English ballad called “The Oxford Girl” with Appalachian versions, and I thought, “She’ll love doing this.” I think the backstory is that a man gets a woman pregnant and doesn’t want to have children with her, so he takes her over to a grave he dug and kills her. She said, “Why would I want to sing about that?” [Laughs] “Think about the story that this is telling!” It made me think about what it was that repelled her. That helped me confront a different point of view.

We also have a 12-minute version of Charley Patton’s “Boweavil Blues.” When I first began working on it, we were communicating by phone and sending MP3s back and forth to each other. She, of course, knew of the song when I mentioned it. She said, “There’s nothing for me there. There are two notes. What am I going to do with that for 12 minutes?” I said, “Don’t worry, I’ve got something.” What I did is I wrote the bass line that went underneath the verses, so that even with just two notes, it kept shifting the way the notes would be heard. It also implied moving around and away from those two notes in a way that made more room, and a nice amount of room to be living in, too. When I sent her the tape, she said, “Okay, I get ya.”

We had the first rehearsal in New York with the whole band, with a string quartet and a rhythm section. Without even trying sketches, she said, “Let’s jump into it!” She sang the whole thing, front to back, and she had developed an entire way of approaching this song all on her own. It’s easy to remember, because at the end of this first run through, I went over and gave her a big kiss and said, “My goodness! What have you done here??” That was a challenge. And it challenged me in terms of what our subjects would be and how they would be presented.

Thanks very much Dick Connette, for chatting with us abut Sonya Cohen Cramer’s music and legacy. Find the music here on BandCamp: https://sonyacohencramer.bandcamp.com/album/youve-been-a-friend-to-me