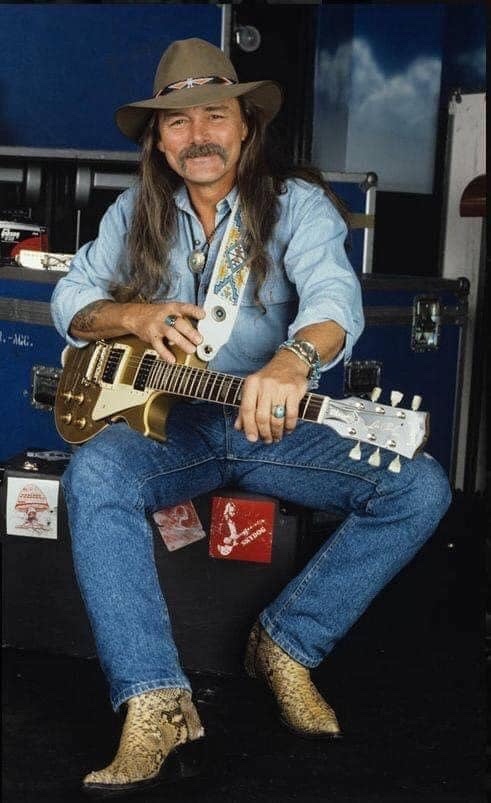

Dickie Betts photo by Kirk West photography

On a weeknight in summer 2002, I was on vacation in Dewey Beach, Delaware. After putting the kids to bed, I headed over to Bottle & Cork where Dickey Betts was playing with his solo band, Great Southern. It seemed like too small a room for someone who had been at the pinnacle of rock stardom. But now he was in a state of exile, estranged from the Allman Brothers Band he co-founded–and where he pioneered twin guitar and harmony virtually authored Southern Rock, a whole genre of American music.

“Dangerous Dan!” somebody yelped to the surprise and delight of his co-guitarist Dan Toler whose eyes revealed startlement at the sound that had the cadence of Forrest Gump. I saw a roadie bring a cold can of Budweiser to the foot of Betts’ amp which caused a few of us near the stage to start talking. After all it was Betts’ struggles with alcohol and drugs that had led to his unceremonious departure from the band. Betts received an unbrotherly fax in 2000 effectively firing him and wishing him well in recovery. Throughout the evening, Betts picked up the can and put his lips on it as if just to taste it —but didn’t drink from it. The temptation must have been so great to just flip the angle of that can as a lifetime burden was playing out in this little dive bar.

Betts’ exile played out over the years. I once heard Gregg Allman interviewed and when he was inevitably asked about why Betts left, he responded curtly: “Listen to the tapes,” a reference to Betts’ live playing. When the interviewer tried to get his composure and lead the conversation, he said, “Once a brother, always a brother” to which he was met with dead silence by Allman.

I came of age in the post-Duane Allman incarnation of the band. My first concert was at the now defunct New Haven Coliseum on the Summer Campaign Tour 1974. After an opening set by Grinderswitch, we waited for the Allman Brothers. And we waited but there was still no Gregg and Dickey. Fans were getting restless and throwing things on stage until promoter Jim Koplik assuaged the crowd and announced that Chuck Leavell, Jaimoe and Lamar Williams, a group of guys who jammed at home in Macon, would play. The Allman Brothers didn’t go on until 9:30 and we didn’t get home until 2 am, a late hour for junior high school students. But I could later say I saw the incarnation of the band that would become Sea Level.

A year later I was 15 and started writing articles about music. I talked myself into my first backstage pass at the same venue. In the backstage halls of the Coliseum during intermission, Betts came offstage and headed straight in my direction on his way to the dressing room . Dressed in an all-white suit, he had the swagger of a star. I had some paper out to take notes and he took my pen and went straight into signing an autograph. I tried my hand at being a journalist and asked him if there would be a second Richard Betts solo album. I suspected he was too drunk when he didn’t answer me and the script of his signature was an ineligible scrawl. But Betts exuded warmth in those brief moments. He and Allman skedaddled but in a hospitality room set-up to the side, I met Chuck Leavell who was ever gracious and posed for a picture.

Flash forward to the Beacon Theater some time in the early Nineties. The reconstituted band was in the early years of their multi-night run in New York City and before showtime out of the corner of my eye I noticed Betts coming out to greet fans before showtime. He knelt down to talk and greeted them, pivoting side to side as he extended each of his hands in a warm embrace as if there was a transference of divine Brotherhood to the faithful in front.

Betts’ death hit us hard this past week. For some reason I played his first solo album, Highway Call the weekend before he passed. I hadn’t listened to it for years and played it back to back with Gregg Allman’s Laid Back and forgot how good these albums were. Betts’ intertwined play with picker Vassar Clements felt transcendent all these years later.

This week was a time to tell stories. Betts’ interview about his friendship with Bob Dylan in Ray Padgett’s book Pledging My Time: Conversations With Bob Dylan Band Members is priceless. Dylan told him he wished he wrote “Ramblin’ Man” but was wary of singing it together live. Betts told him not to worry —it would all come together and they traded verses one night. A video of Betts’ sit down with Dan Rather in 2018 was a reminder of the magic of the Allmans forming. “We didn’t know what we had.”

In my own family, there was a story to share. My wife Kelly’s sister, Jessica, shares the same father, the late Oz Back who once played in Spanky and Our Gang. She remembered how her Aunt Mimi was one of Betts’ back-up singers for years. “I remember sitting in Dickie’s trailer when they performed at Legend Valley. He told me he had a little girl named Jessica, too, and that he’d written a song for her. He said when they played it that day, he’d look for me in the crowd (we were right up front). When “Jessica” started, he looked at me, winked and tipped his hat. I was 10. I’ll never forget it.”

My own memories came flooding back. There’s the memory of entering the Coliseum in 1974 and seeing the Allmans’ stage. For me, it was like seeing the majestic centerfield coming out of Yankee Stadium for the first time. In the long backstage halls of the New Haven Coliseum the next year, I spotted Capricorn Records president Phil Walden. His facial expressions are still ingrained in my mind. They were stoic and I’m sure on that night in 1975 Walden wondered about the future of the band he brought to fame. Over the years I thought about the distance in his eyes, perhaps masking the burden he carried all his life having lost the great soul singer Otis Redding whom he managed until the fateful lane crash in 1968–and then Duane Allman and Berry Oakley just a few years later.

“I’m so glad I was able to have a couple good talks with him before he passed,” Betts said of Gregg Allman after he died. I hope he found some peace and I’m sure he felt whole by the legacy he left behind as his son Duane and Gregg’s son Devon Allman front the Allman Betts band.

There was also the night Susan Tedeschi and Derek Trucks brought Betts up onstage. Betts surmised that the couple, now married with children, met backstage at an Allman Brothers show. He told Relix, “I mostly remember the introduction they gave me that night: ‘Please welcome the great and loveable Dickey Betts.’ I’ve never been called loveable before. I laughed all the way to my amp.”

In his interview with Dan Rather, Betts reflected back to the days when Duane Allman passed and the band brought in keyboardist Chuck Leavell. Betts’ eyes gleamed as he talked about Leavell and what he brought to the band, saying he almost deserved a co-writing credit on “Jessica.”

Leavell, whose footprints are all over Brothers and Sisters as well as Highway Call and Laid Back, is the longtime keyboardist and de facto musical director of The Rolling Stones. This week my best friend who was with me that night on Summer Campaign 1974, shared a Facebook post of footage that circulated from The Rolling Stones rehearsal. The image of the empty Stones stage on the file conjured memories of being at the Coliseum for the first time. On the audio, the musicians go through their tuning for several minutes until Leavell finds the right moment to break in and ask, “Everybody ready?”

He then counts the song down before Mick Jagger sings “Sweet Sounds of Heaven.” In a week where we lost a Brother, there was something comforting about the familiar ritual of musicians rehearsing and getting ready to go on a new tour.

Find recent information on his website here: https://dickeybetts.com

REVIEW: The Allman Brothers Band Down In Texas ’71

I was at that concert at the New Haven Colosseum. My first concert, which was with the ABB and Marshall Tucker, was at Dillon Stadium in Hartford in 1973.

I was there that night in Dewey Beach!