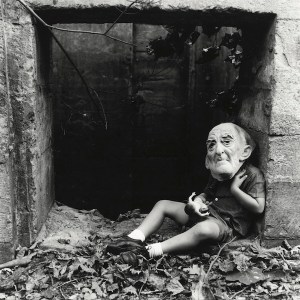

Loose Cattle photo by King Edward Photography

Kimberly Kaye of Loose Cattle on The New Orleans Community Behind Someone’s Monster

New Orleans-based band Loose Cattle will be releasing their third full-length album, Someone’s Monster, on November 1st, 2024, via their new label home of Muscle Shoals-based Single Lock. The album is notable for several reasons, including Loose Cattle moving into focusing on original songs more fully, broadening their sound into more eclectic territory, and having some exciting guests on certain tracks, like Patterson Hood posing as a kind of river demon on “The Shoals” and Lucinda Williams providing extra vocals on their cover of Lady Gaga’s “Joanne.” Evident throughout is the way in which they’ve grown together as a band over their time together and the resultant confidence that makes them more daring in their self-expression.

Fronted by Kimberly Kaye, who has a background in jazz, theater, and punk music, and Michael Cerveris, who’s a Tony and Grammy Award-winner currently starring in the Tammy Faye musical, Loose Cattle has been built upon a community of musical interests and musical support in New Orleans in quite a profound way. Originally welcomed by local musicians in a humbling and kind way, Loose Cattle, and Kaye herself have found that sustaining relationships have made their ongoing musical journey possible. I spoke with Kimberly Kaye about this next step in songwriting, community, and collaboration.

Americana Highways: What sort of time period do these songs hail from? Are you a band who tends to work on songs over a long period of time, or are they from a more recent collaboration?

Kimberly Kaye: It’s a little bit of both in a way that I wouldn’t have predicted. A lot of the writing took place during pandemic lockdown and because of where people are located, and Michael splitting time between New York and New Orleans, he got stuck up North, while the rest of us were in New Orleans. Everybody in the band was in their little bubbles. During that time, we did have extra time to write, which was great, but the problem was that we couldn’t get together as a group and play through them.

Lyrically, and as far as putting together new material, had a lot of time for Michael and I to pass notes back and forth, but then things opened up, although we weren’t still playing shows at that time. When we went into the studio, we had these songs that we’d kind of been working on for two years, but no one had actually worked on together as a unit.

Typically, we would take new material into the studio after playing it live for a bit. But this time we recorded the album, but didn’t get to play it live, really, for another six months. I joked to Michael recently, “Now that we’ve figured it out for the last year, I would really like to go in and re-record it…” [Laughs] And he said, “Absolutely not! Shut it down!” Which is absolutely the right answer.

AH: I’m relieved that you at least allowed yourself to play the songs for the last year, because it has been such a long road to release for you. If you had continued to sit on the songs, that would have been just unfair.

KK: The album itself feels somewhat like a relic, though the songs haven’t changed that much.

AH: I think the liner notes for the album are a kind of “secret handbook” to the album, with so many rich stories behind the songs that you all share. I did see it occasionally mentioned that during recording, “The band had never heard the song before.”

KK: Yes! [Laughs] That happened.

AH: I do feel like that’s kind of exciting, that estuary-like moment when everyone’s finally together for the first time to do this, but also requires a lot of flexibility, and maybe even compassion. It’s difficult to jump on something really fast.

KK: You couldn’t have picked a better word for it, too, “estuary,” because we were in the swamps of Southern Louisiana, literally watching barges go down the river from the studio. Dockside is right on the water in the heart of bayou country. We had the rivers of different people coming in and converging on this Lafayette-area studio. We had to figure the songs out, and we had five days, but it was really thrilling. It may sound corny, but there is something thrilling about watching extremely smart, capable artists make something together.

“Tender Mercy” is my favorite example on the album. I said to Michael, “We need something that is uplifting, but also we’re clearly angry about some stuff. I hear this as a punk, driving thing.” He said, “That’s great.” And we left it with the band, since they were figuring out the orchestrations, and I went to take a nap. We’d been in the studio all day, so I laid down for an hour, then I came back. They were playing this soft, groovy thing. They said, “We’ve got this thing!” It was a completely different animal, and it was so much better. I’ve always thought the best way to get a fantastic tattoo is to go to a great tattoo artist and say, “Do whatever you’re the best at. I’m not going to bother you.” I feel like that’s sometimes what you do when you’re making songs. We handed these sketches over to the band, and they made something completely different than we expected, but I think it’s better for it.

AH: I’m so glad that you mentioned “Tender Mercy.” I listened to the album in order, so I didn’t hear that one until the end. I was knocked over by it, but also kind of washed away by it. It arrives and settles over all the emotions and journeys on these other songs. It’s so calm but it says so much.

KK: I’m happy that you feel that way. I feel like what it’s trying to say is heard better at the tempo, and with the mood there. If it had been that original punkier sound, I don’t think it would have had that impact. I think how we said it on the album is better.

AH: It feels like it’s coming from a place where all the energy has been spent, and that’s a very convincing tone. It makes the argument best. It’s like the last few conversations before dawn when you’ve been up all night.

KK: That song really is supposed to be the end of the conversation when you’ve been up all night. For us, it typically comes back to, “All of this stuff is really bad, but I love you, and let’s take care of each other. See you soon.”

AH: Have you all played that one?

KK: Yes, we have, as a trio, and as a full band. It’s been great to watch people during that bridge section, which we pull the title from, “We’re all someone’s monster.” Watching that line being absorbed and people saying, “Ohhhh,” is awesome.

AH: Geography really affects people and lives, and it’s something that some people are drifting away from, but some are beginning to realize again. I think that geography is something that’s shaped not only your band, but this album.

KK: It’s very fortunate, and it’s also a by-product of New Orleans, which is a quintessential and essential music city, but it’s not known for the type of music that we’re doing. You think of brass bands, you think of Funk. There is a thriving and incredibly competent Americana scene, with some of the best songwriters working together, but what people are looking for when they come to New Orleans is not Americana. I would say that people go to Nashville or Austin interested in seeing Americana music.

Here, you have to work hard to cultivate and keep the Americana scene alive, because it’s not as organic. The way to support the scene here is to be incredibly supportive of each other, to be champions of each other’s work, and to work together. We work to put together festivals. We don’t have a New Orleans Americana festival, so we have to work together to make sure our opportunities aren’t limited. That’s some of what you’ll see in the liner notes, that sense of community.

AH: When you need each other, you are more accepting of each other. It’s probably good for people to be in that situation because it breaks down things we think of as dividing differences. You start to see things differently.

KK: Yes. It’s also understanding that the scarcity mindset is not a healthy mindset anywhere. There are places and times where that’s bred into you that competition is good. But is it? But at least in New Orleans, there’s a centuries-long legacy of people who are self-taught. They didn’t go to Berklee. They learned music because that’s what you generally do. Then a community elder, without being paid, stepped in and said, “Hey, I’ve learned a lot of stuff, here’s something you might not know.”

Something that was really important to the foundation of Loose Cattle is that with the band that you hear now, Paul Sanchez, who was one of the songwriters of Cowboy Mouth for years and is very cherished in New Orleans, welcomed us. I was just in my twenties when I got to New Orleans, and Michael was a Broadway guy, which was a lethal label if you want to make music and have anybody take you seriously. A Tony Award is very bad, giving you that actor-musician label! Paul, however, came from that New Orleans model of, “No, you share the stage, you share your knowledge. That’s the only way that there’s a scene that continues to exist.” He invited us to sing and play with him a lot, and he started promoting our shows. It helped us meet a lot of people. It gave us a seat at the table. We owe a lot to that long history in New Orleans of, “Y’all, we gotta share these resources! If you keep competing, this won’t work!”

AH: I can definitely see how helping other bands out, playing for them as needed, comes back as support for you. That’s a big statement of mutual support. You are what you choose to do.

KK: For me, personally, it gets even deeper, because I spent the better part of 2016 and 2017 in organ failure and was tremendously ill, in and out of hospitals. I lost my home and lost my job. What you’re talking about, for me, and for Michael, was something where the New Orleans musical community and the fanbase that supports music down here, heard that I was very sick and made a GoFundMe for me go viral.

The only reason that I’m alive today, and the only reason that I get to make music with these guys is because a bunch of generous, most of whom were not affluent, pooled their resources. I was a stranger to most of them, but they made sure someone else had to medical care to survive. Michael has always been generous, but I now feel a lifetime of indebtedness, that when people need help, you help. The more that you give, authentically, without expecting anything back, the better it is for everyone. It’s not transactional for us.

AH: The story about Louis Michot in the liner notes is a good example of that, how he came to play on the album. I saw that he just happened to be in town that day and turned up with a bunch of food for you.

KK: Yes! There’s nothing quite like having a born-and-bred Cajun burst through the door of your swamp studio with a whole armful of food. This is just what happens! Louis is one of those people who was very welcoming and kind to us when we arrived in New Orleans. In the spirit of talking about communities, Rurick [Nunan] is also a very sought-after fiddler here who plays with a couple groups. Part of being a New Orleans band is that you can’t all gig on Friday nights, because you share members. Louis is someone who has been kind enough to step in our songs and replace Rurick on the nights when he’s out touring with someone else. That’s part of the same thing, which is that it takes a community to keep this scene alive.

Thanks very much for chatting with us, Kimberly. You can find more information here on the Loose Cattle website: http://www.loosecattleband.com/

You can find the album here: https://link.singlelock.com/loosecattle