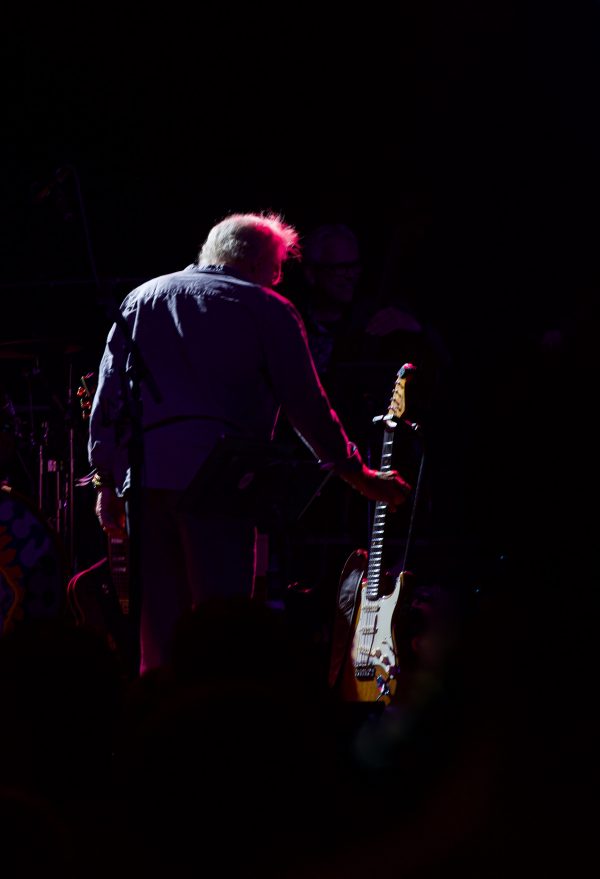

Bob Weir photos by Melissa Clarke

Fare Thee Well, Bob Weir

I don’t remember the exact year but somewhere in the early Nineties I left Madison Square Garden in New York snapping my fingers as Bob Weir led the Grateful Dead through an exhilarating finale “One More Saturday Night.” I’m pretty sure it was a Friday night (or almost Saturday Night” to borrow from John Fogerty) but Weir declared the weekend was in. As Weir streaked and shrilled in rock and roll abandon it was like he was in a trance like he used to get charging through Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away.”

The thing about Bob Weir—who we referred to as Bobby as if we were on a personal first name basis—is that his rock and roll prowess wasn’t even the best he had to give. It was a ritual closing your eyes and picking out Weir’s subtle rhythm guitar chords that formed their own mosaic of soundscapes that underpinned the bursts of leads from Jerry Garcia. Sometimes Weir was so subdued and blended in so much that you’d only realize how substantive he was if he was unplugged. Bob Dylan called him an unorthodox rhythm player and said he played like Charlie Christian at the same time.

And there were those magnificent songs that were transcendent. “Looks Like Rain” and “Cassidy” from his solo album Ace that were so good they defined the Dead for the next few decades, with his crowning masterpiece “Weather Report Suite” coming a few years later. Long before there was Americana the genre, Bob Weir was its godfather of a genre in waiting. When Weir took on “Black Throated Wind,” “Mexicali” and Marty Robbins’ murder ballad “El Paso,” immersed in his Western interpretations, it seemed all the more authentic from someone who spent time as a ranch hand in his youth.

At the age of 14 (and with eternal gratitude to my eight grade math teacher) I count myself lucky enough to have gone to the top of the mountain with the Dead when I saw the Dead play through their enormous wall of sound at Dillon Stadium in Hartford in 1974 shortly after From The Mars Hotel was released. Never did I hear sound as clear or pure and everything ever since has felt anticlimactic. Frozen in my memory were all the smiles that emanated onstage that night between Garcia, Phil Lesh, Weir and Donna Godchaux —with Weir being the last of the latter three to leave us within the last year.

But it was the film documentary about Weir’s life, The Other One, mesmerized me as much many years later. In the aftermath of Jerry Garcia’s death, Weir was a wandering soul who grieved on the wildness with the loss of his lifelong partner and mentor. The story tells of the reunion with Weir’s birth father and meeting his wife who recognized his deep yearning to love again in the wake of Garcia’s passing. In those two hours you felt emotionally transformed and came away with a better understanding of the meaning of life.

As the years moved on and Weir pursued post-Dead incarnations The Other Ones, Furthur and Dead and Company, the man in cargo shorts was still clinging to the eternal youth he’d been blessed with. Men’s Health did a fitness profile of him abounding up the hills and steep incline of the Jiffy Live amphitheater in Bristow, Virginia. It’s where he looked out to a sea of Deadheads, leading Dead & Company and welcoming John Mayer into the family.

Over the years the self-deprecating Weir delighted Deadheads who dissected when he’d flub a line or lyrics like they were tallying the baseball box score. Neither his miscues nor transcendent moments phased him.

“Bobby was completely allergic to compliments in the most endearing way,” guitarist Trey Anastasio reflected. “I’d say, ‘Man, that guitar riff you were doing on that song sounded really killer’ and he’d respond, ‘Well, I’m sure I’ll fuck it up next time.’ I loved that about him.”

As Weir aged and developed a thick white beard that enveloped his face like he was the ghost of Grateful Dead past, he never lost his curiosity to grow musically, jamming and guesting with younger generations and clocking in at seven years with the Wolf Brothers. As AH writer Andrew Blanton called it, it was “the freedom Weir has without the Grateful Dead name attached.”

The runway was felt by the band itself.

“Night after night,” wrote Don Was, “he taught us how to approach music with fearlessness and unbridled soul – pushing us beyond what we thought was musically possible. Every show was a transcendent adventure into the unknown.”

Weir’s ode to the counterculture he helped create was vast, from the anthemic “Truckin’,” through to in his later years when we’d count ourselves fortunate to bask in the sheer beauty of hearing an almost spoken recitation of Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” or “Desolation Row.” Left behind are not only fans but what Blanton described as “a caravan of bohemians, hitchhikers, bikers, soul-searchers, music obsessed fans and vendors who have followed Bob Weir around for more than fifty years–setting up mobile cities in the parking lots and campgrounds that surround the venues.”

During a week when an ICE agent murdered a woman in Minneapolis with seeming impunity, Weir’s loss felt like another blow to the good side of a country losing its moral center. If the Dead never wanted to use the stage as a political pulpit, Weir emerged as a soft spoken but staunch advocate standing for social issues. During the protests against racism and NFL players knelt during the national anthem, Weir was asked about it and he preached restraint and brought Ghandi into the conversation. The advice still seems prescient.

“There are folks who would love nothing more than to make this into a civil war basically,” Weir said. “And it is a ‘civil war,’ but their armaments are rubber bullets and tear gas and that kind of stuff. If you’re on the side of the peaceful protestor, your armament is ideas, and I’ve gotta say that we’ve got them outgunned.”

Ultimately complications from cancer assisted in what got him just like diabetes did to his partner and mentor Jerry Garcia. In the end they succumbed to two of the most common chronic diseases that affect us all. But like Pete Seeger who lived into his nineties, we all bought into the illusion that they’d defy time and go on forever. It might sound selfish but with his contemporaries like Bob Dylan and Mick Jagger performing into their Eighties, it felt like at 78, Weir was still relatively young and there were still miles in the tank … .and playing on another Saturday night.

Just one more Saturday night.

As of Saturday January 10, it just wasn’t meant to be.

Find some more of our coverage here: Show Review: Bob Weir & Wolf Bros at Pier Six Pavilion here: Show Review: Bob Weir at the Moody Theater here: Show Review: Dead and Company, Two in Texas here: Show Review: Bob Weir and Wolf Bros’ Sunday Show at Beacon Theatre Lives Up To The Hype here: In Bristow, Dead & Company Skip The Goodbyes here: Show Review: Bobby Weir and The Wolf Brothers in Dallas